Unfortunately for asthma sufferers and those looking to develop new treatments to help them, animal models traditionally used to test potential new drugs don't always mimic human responses. Joining lungs and guts, scientists at Harvard's Wyss Institute have now developed a human airway muscle-on-a-chip that could help in the search for new treatments for asthma. The device accurately mimics the way smooth muscle contracts in the human airway, both under normal circumstances and when exposed to asthma triggers.

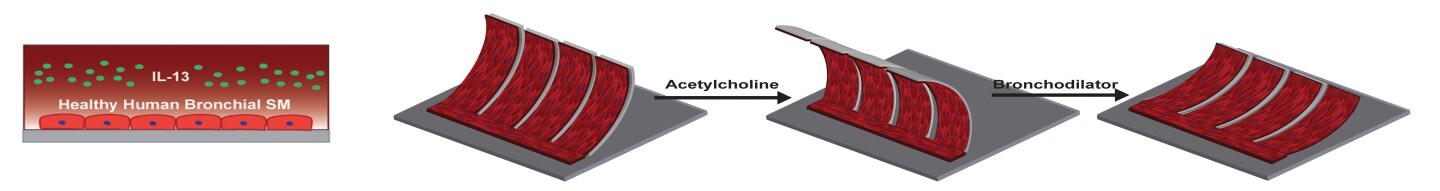

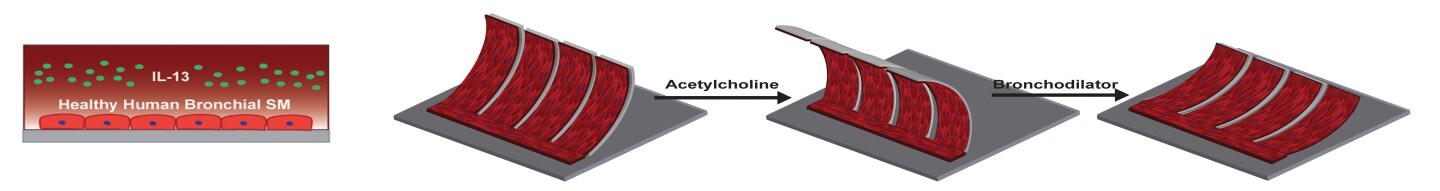

The device consists of a soft polymer well mounted on a glass substrate and contains an array of microscale, engineered human airway muscles that are designed to mimic the laminar structure of the muscular layers of the human airway. The team got the chip to mimic a typical allergic asthma response by first introducing to the chip interleukin-13 (IL-13), a natural protein that is a mediator of allergic inflammation often found in the airways of asthmatics, and then introducing acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that causes smooth muscle to contract.

In response, the airway muscle-on-a-chip hypercontracted, with the soft chip curling up when exposed to higher doses of acetylcholine. The researchers were able to reverse this effect and trigger the muscle to relax by using β-agonist drugs used in inhalers. Importantly, that amount of contractile stress was directly related to the dosage levels of the drugs.

The chip was also able to give an insight into the cellular and subcellular responses within human tissue during an asthmatic event. The researchers confirmed that the smooth muscle cells grew larger over time in the presence of IL-13, which is something also found in the airways of asthma patients. The also noticed that super-thin cellular components within smooth muscle cells involved in muscle contraction, known as actin fibers increased in alignment, which is also consistent with the muscle in the airway of asthma patients.

Going further, the researchers observed changes in the expression of contractile proteins called RhoA proteins in response to IL-13. RhoA proteins have previously been implicated in the asthmatic response, but details regarding their activation and signaling have proven difficult to nail down. To do this, the researchers introduced a drug called HA1077. This is a drug that targets the RhoA pathway, but is not currently used to treat asthmatic patients.

The team found that HA1077 reduced the sensitivity of the asthmatic tissue in response to the asthma trigger, with preliminary tests indicating that a combined therapy of HA1077 and a currently approved asthma drug worked better than the single drug by itself.

"Asthma is one of the top reasons for trips to the emergency room – particularly for children, and a large segment of the asthmatic population doesn't respond to currently available treatments," said Wyss Institute Founding Director Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D. "The airway muscle-on-a-chip provides an important and exciting new tool for discovering new therapeutic agents."

The team's research is published in the journal Lab on a Chip.

Source: Wyss Institute

Unfortunately for asthma sufferers and those looking to develop new treatments to help them, animal models traditionally used to test potential new drugs don't always mimic human responses. Joining lungs and guts, scientists at Harvard's Wyss Institute have now developed a human airway muscle-on-a-chip that could help in the search for new treatments for asthma. The device accurately mimics the way smooth muscle contracts in the human airway, both under normal circumstances and when exposed to asthma triggers.

The device consists of a soft polymer well mounted on a glass substrate and contains an array of microscale, engineered human airway muscles that are designed to mimic the laminar structure of the muscular layers of the human airway. The team got the chip to mimic a typical allergic asthma response by first introducing to the chip interleukin-13 (IL-13), a natural protein that is a mediator of allergic inflammation often found in the airways of asthmatics, and then introducing acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that causes smooth muscle to contract.

In response, the airway muscle-on-a-chip hypercontracted, with the soft chip curling up when exposed to higher doses of acetylcholine. The researchers were able to reverse this effect and trigger the muscle to relax by using β-agonist drugs used in inhalers. Importantly, that amount of contractile stress was directly related to the dosage levels of the drugs.

The chip was also able to give an insight into the cellular and subcellular responses within human tissue during an asthmatic event. The researchers confirmed that the smooth muscle cells grew larger over time in the presence of IL-13, which is something also found in the airways of asthma patients. The also noticed that super-thin cellular components within smooth muscle cells involved in muscle contraction, known as actin fibers increased in alignment, which is also consistent with the muscle in the airway of asthma patients.

Going further, the researchers observed changes in the expression of contractile proteins called RhoA proteins in response to IL-13. RhoA proteins have previously been implicated in the asthmatic response, but details regarding their activation and signaling have proven difficult to nail down. To do this, the researchers introduced a drug called HA1077. This is a drug that targets the RhoA pathway, but is not currently used to treat asthmatic patients.

The team found that HA1077 reduced the sensitivity of the asthmatic tissue in response to the asthma trigger, with preliminary tests indicating that a combined therapy of HA1077 and a currently approved asthma drug worked better than the single drug by itself.

"Asthma is one of the top reasons for trips to the emergency room – particularly for children, and a large segment of the asthmatic population doesn't respond to currently available treatments," said Wyss Institute Founding Director Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D. "The airway muscle-on-a-chip provides an important and exciting new tool for discovering new therapeutic agents."

The team's research is published in the journal Lab on a Chip.

Source: Wyss Institute